DECEND ALONG MY EYELASHES

Exhbition and performanceIn collaboration with Petter Ballo and Christian Tony Norum

UKS, Oslo, 2014

Performance starring Helge Haaland (double bass), Petter Width Kristiansen (actor)

Installation view

Installation view Installation view

Installation view  Installation detail, Sledge Cloud, oil paint on canvas (Norum), Self regulating string instrument, (Bakketun)

Installation detail, Sledge Cloud, oil paint on canvas (Norum), Self regulating string instrument, (Bakketun)  Self regulating string instrument, strings, ventilator with rubber hose and bamboo, contact microphones, 600 x 300 x 50 cm

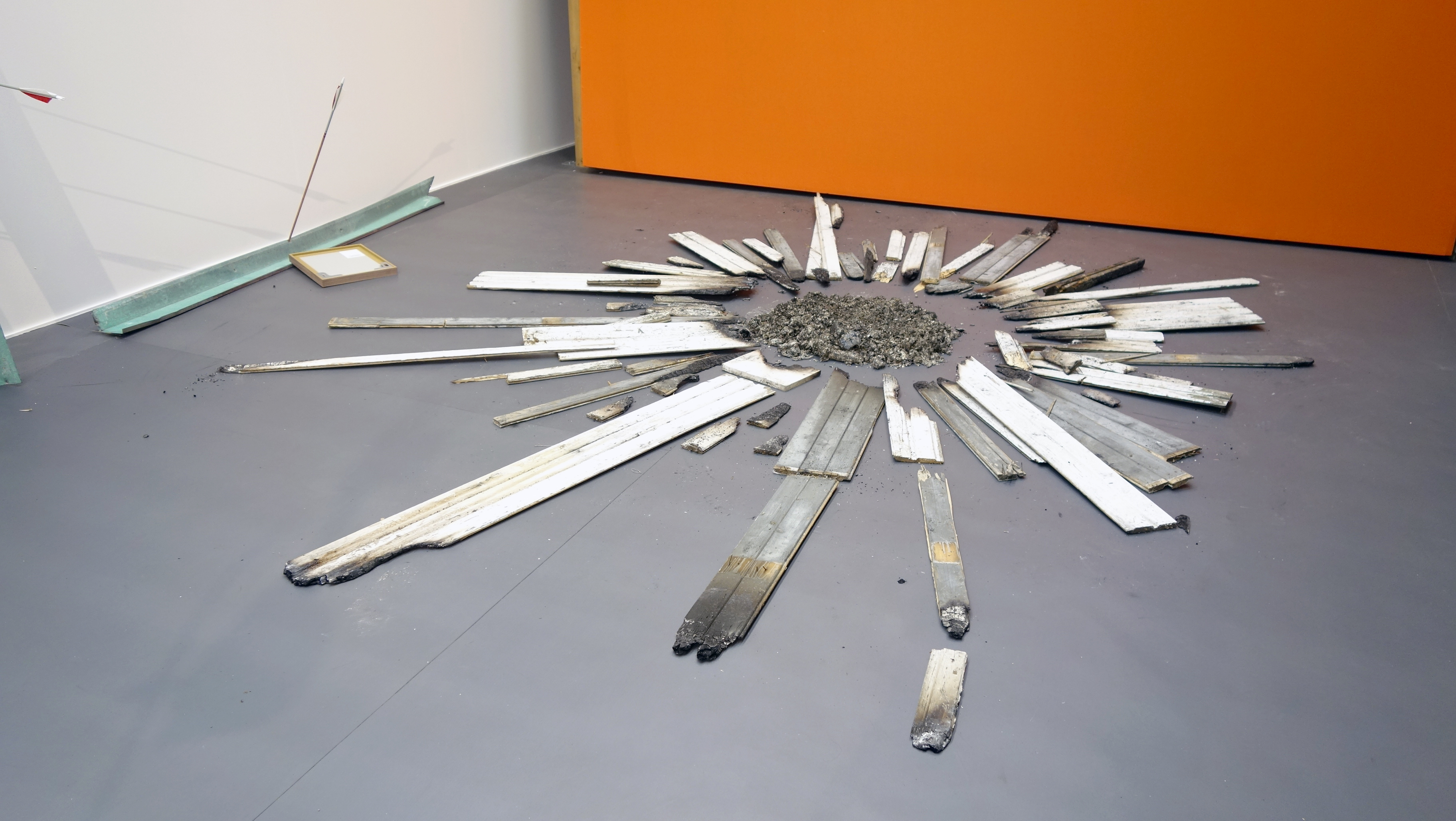

Self regulating string instrument, strings, ventilator with rubber hose and bamboo, contact microphones, 600 x 300 x 50 cm Installation detail, burned wood

Installation detail, burned wood  Untitled, (Bakketun), bamboo, metal springs, 200 x 75 cm

Untitled, (Bakketun), bamboo, metal springs, 200 x 75 cm Installation detail, (Bakketun and Norum) oil on canvas and water colors

Installation detail, (Bakketun and Norum) oil on canvas and water colors

Installation detail, Zurich (Bakketun/Norum), water color, garage door streched with canvas from the Munch 150 exhbition (Norum/ Ballo)

Installation detail, Zurich (Bakketun/Norum), water color, garage door streched with canvas from the Munch 150 exhbition (Norum/ Ballo) Installation view

Installation view

Installation detail, (Ballo/Norum) copper sculpture made from the roof of the Museum of Contemporary Art

Installation detail, (Ballo/Norum) copper sculpture made from the roof of the Museum of Contemporary Art  Cut the roof, (Norum/Ballo), copper sculpture made from the roof of the Museum of Contemporary Art

Cut the roof, (Norum/Ballo), copper sculpture made from the roof of the Museum of Contemporary Art Video documentation of exhibition and performance

Performance detail

Performance detail Performance detail

Performance detail

Performance detail

Performance detail

Performance detail

Performance detail

Performance detail

Performance detail

photo: Roderick Hietbrink/ UKS and private

Press release DESCEND ALONG MY EYELASHES

ANDREA BAKKETUN, PETTER BALLO OG CHRISTIAN TONY NORUM

11. november – 16. november 2014 I Åpning / performance 11. november kl. 18.00

Jenny Kinge

Med samarbeidsutstillingen Descend along my eyelashes inntar Andrea Bakketun, Petter Ballo og Christian Tony Norum UKS over fem dager, hvor de innlosjeres i en fordums dansesal dypt inne i institusjonens labyrintiske midlertidige bygg på Tullinløkka i Oslo. Med speil, dansestenger og garderobeinnretninger som scenografi, presenterer kunstnerne en undersøkelse av performancens logikk og potensial til å fremstå som en egen virkelighet – 2 eller snarere en eventyrverden. En rekke ulike tidsepoker og karakterer trekkes inn i fortellingen: Utstillingstittelen er hentet fra en gammel amerikansk myte, mens griffen, fabeldyret som skuer utover Tullinløkka fra taket til nabobygget Nasjonalgalleriet, har stått modell for en av utstillingens skulpturer. Skikkelser fra boken Gamle Kristianiaoriginaler fra 1922 har vært med på å forme performancen kunstnerne gjør på åpningskvelden, hvor karakterer som «Grønlands-Ibsen» og «Wergelandsgutten» tolkes med både humor og alvor. Edvard Munch er skyggeaktig tilstede i Christian Tony Norums verk, som tar i bruk tekstiler fra jubileumsutstillingen Munch 150. Tekstilene trekkes over en fjernstyrt garasjeport som lar seg åpne og lukke, og fremkaller den avgrensede flatens muligheter, som fysisk overflate og mental inngangsport. Andrea Bakketun har konstruert et overdimensjonert strengeinstrument som spennes opp gjennom store deler av rommet. Under åpningskveldens performance får instrumentet rollen som hendelsens dirigent; tilfeldighetene i instrumentets komposisjon danner utgangspunkt for intuitive hendelsesforløp. Petter Ballo bearbeider på sin side den litografiske teknikkens metode i sine lysende tegninger – fremfor å tegne i stein har han risset i de tidligere dansespeilene som befinner seg i rommet og lyssatt dem bakfra. I siderommene til dansesalen presenteres 8mm-filmer av Ballo, med elementer fra performancer kunstnerne har gjort sammen tidligere. Descend along my eyelashes gransker et vidt spekter av historier, myter og drømmer, som utvikler seg til en sammensatt gjenfortelling.

Gjestekurator for Descend along my eyelashes er Jenny Kinge. Produksjonen er støttet av Norsk Kulturråd. Utstillingen Descend along my eyelashes er en del av UKS’ vinterprogram 2014/15. I tillegg til hovedprogrammets to store soloutstillinger med Marthe Ramm Fortun og Kjersti Vetterstad, bys det her på boklanseringer, performance, utstillinger av kortere varighet, filmvisning og andre events. Programmet er juryert av UKS’ Jury

A Fickle Troupe

Essay by Stian Gabrielsen

There’s an undeniable irony in setting out to write about performance works and then only have access to them via documentation—and scarce documentation at that. I’ve never actually witnessed any of Petter Ballo, Andrea Bakketun and Christian Tony Norum’s performances first hand. Although it makes me unfit to write about them, these dissuasive circumstances has the advantage that they make clear what we intuitively consider an important aspect of performance art—perhaps even a main (if somewhat obvious) qualifier: that it takes place at a specific time and place. A performance can tour, of course, like a theatre play, but unlike a traditional play—which refers back to a detailed script and therefore is anchored in something unchanging, which it also serves to mediate—when we talk of performance works we tend to think of them as unique events that are not supported by scripts in the same sense as theatre plays (even when they are, as is often the case). Perhaps it has to do with how performance art has always given special attention to the notion of concrete presence; it argues for a different mode of appreciation than theatre, one more attuned to the reality of the performing bodies—their here and now. With this emphasis on “flesh”, the internal relations of the medium of performance become elastic; on a physically concrete level each iteration of a specific performance is influenced by so many unpredictable factors that it is bound to change from one day to the next. One could of course try to weed out the site-responsive and indeterminate character of the performance-act through careful scripting and obsessive rehearsals, and by staging it in controlled surroundings, like on a stage—then you would have a piece of performance art that in important respects resembled traditional theatre. On its second staging, however, the performance would nonetheless have changed, just by virtue of being a performance. It might not admit as much, there might not even be any perceptible change to speak of—in principal, however, change has still taken place.

From where I’m sitting—watching vimeo-uploads—this account of performance as an irreducible event, where the event is not corresponding to a fixed script, seems something that Bakketun, Norum and Ballo are attuned to. One symptom of this indeterminacy is how they are not a fixed group; the cast in their performances vary. They are individuals who occasionally come together and perform alongside each other. Their performances are clearly influenced by this informality—their work could be described as a kind of tapestry of overlapping, yet disparate actions. There is no climax, no attempt to guide attention for longer periods—not even the flesh of the performer offers a proper focal point. (Yes, sometimes they take their shirts off—flirting with the performance artist’s known proclivity for nudity—but their actions are always directed at an external object, or prop.) Their dispersed and prop-littered mise-en-scènes dissolve the performance into a litany of diffused actions. It is hard to pin down what exactly it would be in this cacophonous display that merits your prolonged attention as spectator. These performance-tapestries inspire the viewer to digress, much like when engaged in web browsing. Instead of counteracting the unsurveyable nature of their performances by documenting them with an aim to render the reproduction as legible and informative as possible, their documentations tend to elaborate on the digressiveness of the works instead—often resulting in imagery that appear more like a continuation of the creative gesture than an attempt to capture and circumscribe it. Two examples: The video documentation of the performance The Dogs from Caracas—a performance Ballo and Norum did with Henrik Lie at Roma Contemporary Art Fair in 2012—consists of a combination of video and what appears to be 8mm film edited together to form a seductive montage, scored by Lie’s brooding guitar. The performance Reisebrev mangesteds fra—a collaboration between Norum, Bakketun and Silje Linge Haaland, performed in conjunction with the exhibition Christian Krohg: Tiden rundt Kristiania-bohemen at Kunstforeningen Gammel Strand in Copenhagen in 2014—is presented with an emphasis on material captured with a spy-camera wielded on a long camera rig— amended with bass strings and transformed into a motorised musical instrument.

Spy-cameras often serve the purpose of surveilling without the target of this surveillance being aware that she is being watched. As such, it points to a viewing situation where the performance-aspect of the act is involuntary. The kinds of activity that spy-cameras are designed to capture are acts that the perpetrator would like not to be seen doing. In reality, though, what happens most of the time under the gaze of a hidden camera, is nothing out of the ordinary; the incriminating or spectacular event that we are spying for will only take place once in a while—or not at all. The performances of Bakketun, Ballo, Norum (et al.) typically involve actions that are associated with the innocuous and leisurely: They paint, play music, read, serve food, as well as indulge a host of more idiosyncratic but no less innocent and fickle activities—like Norum tapping distractedly on a suitcase while Ballo writes “dow” across his back with sunscreen (The Dogs...). In Reisebrev... the theme of bearing witness to the arbitrary was further emphasised by how the audience had to wear survival blankets over their heads, impairing their vision, while the spy-camera circled above as a kind of disembodied surrogate viewer: present but oblivious. Off to the side a woman with a trained falcon on her arm sat still—jokingly kept company by a can of Falcon beer. The idle falcon might symbolise a lack of “visual prey”—or perhaps a pacifying abundance of it. The bird also has a precursor in a pigeon that has figured in the work of Norum (En due intervjuer Jens Bjørnebo og E. Munch, 2012)—lured into his studio to perform as a kind of inattentive and accidental witness to his paintings and playback of old recordings of Munch and Bjørnebo. Obscure biographical material and anecdotes, like these recordings, pervade their 2 practice. In Descend along my eyelashes this is evidenced by the references to characters from Rudolf Muus’ book Kristiania-originaler, among other things.

Taking a break from writing this short essay and going out to an opening, I ran into Norum and Bakketun. I apologised for having pushed the deadline—not to worry, they said. They had just finished putting up the show, and were exhausted. There was some talk about a huge garage-door that Norum had almost broken his back trying to install. He described to me how he and Ballo had picked it up at a farm—he also mentioned a bonfire, but his words were constantly drowned out by the surrounding racket and I kept having to ask him to repeat; what bonfire? Where? At the farm? The farmer was an interesting guy, I think Norum said, and his father had been a criminal ... Or was that someone else's father—or grandfather? And then he segued into a story about how Walter Benjamin had tried to flee Europe during World War II, but the boat he was on was caught just off shore and he was sent to German-occupied France, where he shortly after killed himself. This story it seemed, was also somehow part of their exhibition, though it was unclear in what way. Then Bakketun showed me some pictures of the garage-door on her phone. Unfortunately, the pictures were very tiny. The door had been stretched with an orange fabric, a leftover from the Munch 150 exhibition at the Munch museum last year. Before we parted Bakketun invited me to stop by UKS around noon the next day, so I’d have a chance to take in the actual works on show before finishing up my text. Obviously, the objects were considered more than mere props and backdrops to a performance. I enthusiastically accepted the invitation, as I imagined it would prove helpful to see the works. Regrettably I never made it there; I had committed to other plans, which I’d simply forgotten. Bakketun had mentioned, however, that a lot of the stuff on show was production from previous performances, and this got me thinking about their performance in Prague with Christian Hennie and Tereza Erbenova (Touristification when the storm wallows the house, 2013), which—judging from the four minute clip I’d seen—in a very overt manner, utilised the performance as a site for an incessant, mechanical producing. A factory-like atmosphere was induced by one of Bakketun’s motorised spinners, suspended right above an indiscernible object, which it drummed a repetitive, clanky soundtrack out of. (The first work I ever saw by Bakketun was a deadpan video documentation showing a similar motorised contraption flapping around inside a kitchen sink, producing a sound much like this one.)

The exhibition at UKS takes its title from a Native American myth called The Man Who Acted as Sun. To “descend along my eyelashes” is what the sun offers his wife and son as a means of transportation to get back down to earth. (His eyelashes are his rays). Much like a cat’s whiskers, our eyelashes function as a sensor that notifies us when a threatening object—like an insect or a grain of sand—is near, so we can lower our eyelids. The eyelid is one of the few external parts of our anatomy which movements we are largely unaware of, as well as not in control of. Its task is to protect and provide moisture to the eye, to keep its function intact. If the eyelash serves as trigger, to “descend along it” would mean to attempt to achieve visual contact without causing a defensive response. In this case, the offer is for the audience to descend along the eyelashes of the performers —to enter their eyes—an illogical switch that perhaps is meant to, again, invite digression.